Introduction: Why Crawl Space Insulation Matters

When it comes to home improvement, crawl spaces are often out of sight and out of mind. Yet, they play a pivotal role in your home’s energy efficiency, indoor air quality, and even structural longevity. Properly insulating your crawl space can prevent energy loss, protect against moisture damage, reduce allergens, and create a more comfortable living environment. However, many homeowners overlook this crucial area, fall prey to persistent myths, or make costly mistakes by choosing the wrong materials or methods. In this comprehensive guide, we’ll walk you through the step-by-step process of insulating a crawl space, provide a detailed breakdown of material and installation costs, and debunk some of the most common misconceptions. Whether you’re a seasoned DIYer or considering hiring a professional, this article equips you with the knowledge to make informed decisions and avoid pitfalls that could impact your home’s performance for years to come.

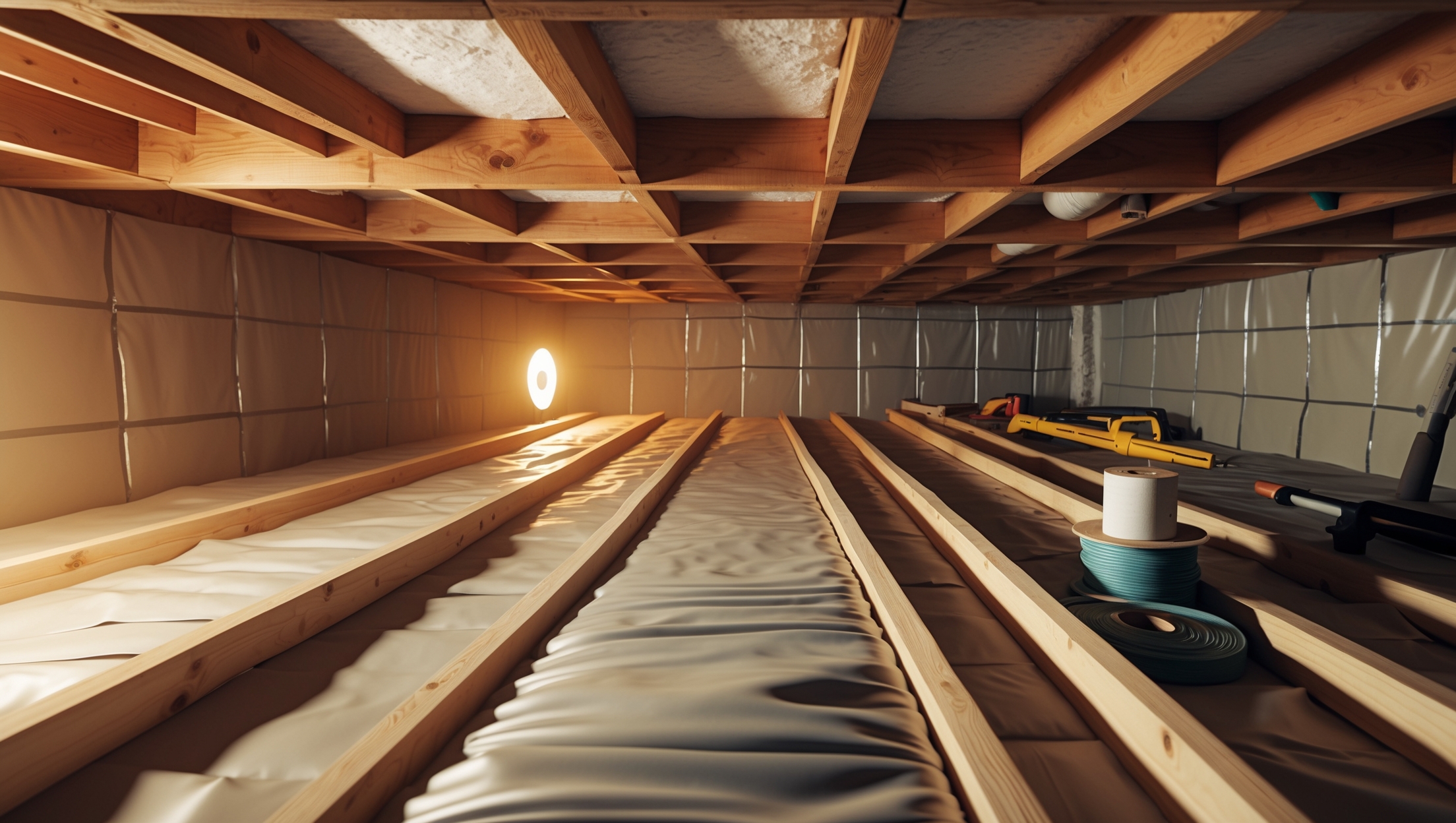

Understanding Crawl Spaces: Types and Challenges

What Is a Crawl Space?

A crawl space is a shallow, unfinished area beneath a house, typically between the ground and the first floor. It provides access to plumbing, electrical wiring, and HVAC systems, but can also be a source of cold drafts, moisture, and pests if left uninsulated or improperly sealed.

Types of Crawl Spaces

- Vented Crawl Spaces: Feature exterior vents intended to allow air circulation. Common in older homes but prone to moisture issues in humid climates.

- Unvented (Sealed) Crawl Spaces: No exterior vents; encapsulated to control moisture and temperature, often preferred in modern construction for energy efficiency.

Common Problems in Crawl Spaces

- Moisture intrusion leading to mold and wood rot

- Heat loss and cold floors above the space

- Pest infestations

- Poor air quality due to dust and allergens

Step-by-Step Guide: How to Insulate Your Crawl Space

Step 1: Assess and Prepare the Space

- Inspect for water leaks, standing water, or signs of mold.

- Repair any plumbing or drainage issues before proceeding.

- Remove debris and old insulation materials.

Step 2: Address Moisture with a Vapor Barrier

Install a durable, 6-mil or thicker polyethylene vapor barrier directly over the soil. Overlap seams by 12 inches and tape them securely. Extend the barrier up the walls at least 6 inches and anchor with construction adhesive or mechanical fasteners.

Step 3: Choose the Right Insulation Material

- Rigid Foam Board: Preferred for sealing crawl space walls. Provides high R-value per inch, resists moisture, and deters pests.

- Spray Foam: Excellent for air sealing around rim joists and tight spaces. Expensive but effective.

- Fiberglass Batts: Commonly used between floor joists in vented crawl spaces, but must be kept dry to avoid mold.

Step 4: Insulate Crawl Space Walls (Recommended for Unvented Spaces)

- Cut rigid foam boards to fit between the floor and top of the masonry wall.

- Attach boards to walls with construction adhesive or mechanical fasteners.

- Seal all seams with HVAC tape or spray foam to prevent air leaks.

Step 5: Insulate Between Floor Joists (For Vented Spaces)

- Install unfaced fiberglass batts snugly between joists, ensuring full contact with the subfloor above.

- Support insulation with wire hangers or netting.

- Do not compress the insulation; maintain its full loft for maximum effectiveness.

Step 6: Air Seal and Protect

- Use spray foam or caulk to seal gaps around rim joists, utility penetrations, and sill plates.

- Install insulation over rim joists with spray foam or cut-to-fit rigid foam.

Step 7: Encapsulate for Maximum Protection (Optional but Recommended)

Encapsulation involves fully sealing the crawl space with a vapor barrier on floors and walls, often coupled with a dehumidifier. This method offers the highest protection against moisture and heat loss, especially in humid or variable climates.

Material and Installation Cost Breakdown

Material Costs (per 1,000 sq. ft. Crawl Space)

- 6-mil Polyethylene Vapor Barrier: $100–$200

- Rigid Foam Board Insulation (R-10): $600–$1,000

- Fiberglass Batts (R-19): $500–$800

- Spray Foam (for rim joists): $100–$200 (DIY kits)

- Adhesives, Tapes, Fasteners: $50–$150

- Dehumidifier (if encapsulating): $300–$1,200

Professional Installation Costs

- Basic Insulation Only: $1,500–$3,000

- Full Encapsulation: $5,000–$15,000 (includes moisture control, sealing, dehumidifier, and insulation)

DIY can save on labor, but be prepared for physical work and tight spaces. Always wear protective gear (respirator, gloves, coveralls) when handling insulation materials.

Common Myths About Crawl Space Insulation: Debunked

Myth 1: “Crawl Spaces Need Vents to Prevent Moisture”

While once standard, research and building codes now favor sealed, unvented crawl spaces in most climates. Vents often introduce more humidity, leading to mold and rot. Encapsulation and mechanical dehumidification are more effective for moisture control.

Myth 2: “Fiberglass Batts Are Fine for Any Crawl Space”

Fiberglass batts can trap moisture and foster mold if used in damp crawl spaces or installed on the underside of floors without air sealing. Rigid foam or spray foam is better for moisture-prone areas.

Myth 3: “Insulating the Floor Above the Crawl Space Is Enough”

Insulating only the floor may not address air leaks or moisture issues. For best results, insulate crawl space walls and air seal rim joists, then add a vapor barrier and consider encapsulation.

Myth 4: “DIY Insulation Is Always Cheaper and Just as Good”

DIY is cost-effective if you have the skill and tools, but mistakes in air sealing, vapor barrier installation, or insulation type can lead to bigger problems and higher long-term costs.

Best Practices for Crawl Space Insulation

Climate Considerations

- Cold Climates: Insulate crawl space walls and rim joists with rigid foam; encapsulate to prevent cold floors and frozen pipes.

- Hot, Humid Climates: Encapsulate crawl spaces with vapor barriers and dehumidification to control moisture and prevent mold.

- Mixed Climates: Follow local code recommendations and focus on air sealing and moisture control.

Ventilation and Moisture Control

- Seal exterior vents unless required by code.

- Install a dehumidifier if encapsulating, especially in humid regions.

- Direct downspouts and landscape grading away from the foundation.

Inspection and Maintenance

- Inspect crawl space annually for signs of moisture, pests, or insulation damage.

- Repair vapor barrier tears and reseal insulation as needed.

- Test dehumidifiers regularly if installed.

Compliance, Permits, and Safety Essentials

Permitting Requirements

- Some municipalities require permits for insulation or encapsulation projects, especially if electrical or structural changes are involved.

- Check with your local building department before starting.

Building Code Considerations

- Follow International Residential Code (IRC) or local amendments for insulation R-values, vapor retarder requirements, and fire safety.

- Install ignition barriers over foam insulation if required by code.

Safety Checklist

- Wear a respirator and gloves when handling insulation or chemicals.

- Use knee pads and adequate lighting in crawl spaces.

- Check for exposed wiring or pests before work.

- Never block access to mechanical systems or vents needed for combustion appliances.

Conclusion: Smart Insulation for a Healthier Home

Proper crawl space insulation is an investment that pays dividends in comfort, energy savings, and peace of mind. By following the step-by-step process outlined above—addressing moisture first, choosing the right materials for your climate, and sealing air leaks—you can transform a neglected crawl space into a well-protected foundation for your home. Ignore the myths: modern building science favors encapsulated, insulated crawl spaces over vented, fiberglass-filled ones in most situations. While the initial cost can be significant, especially with professional encapsulation, the long-term benefits include lower utility bills, healthier indoor air, and reduced risk of structural damage from moisture or pests.

Before you begin, consult your local building codes and consider a professional assessment if your crawl space shows signs of chronic moisture or structural problems. For DIYers, meticulous preparation and adherence to best practices are crucial. Remember, a crawl space isn’t just a storage area—it’s a critical part of your home’s building envelope. Treat it with care, and you’ll enjoy a safer, more comfortable living environment for years to come.

I noticed you mention both vented and unvented crawl spaces as having different insulation needs. How do I tell which type mine is if my house is from the 1970s, and does the preferred insulation method change if I want to switch from vented to sealed?

To determine if your crawl space is vented, look for vents on the exterior walls of the foundation—these are usually metal grates or openings. Homes from the 1970s often have vented crawl spaces, but it’s best to check. If you switch to a sealed (unvented) setup, the preferred insulation method does change: insulation is usually applied to the crawl space walls rather than the floor, and a vapor barrier is added to control moisture.

Could you clarify if there are specific insulation materials that work better for vented versus unvented crawl spaces, especially in homes located in more humid regions? I am curious if the approach to moisture control should differ based on the crawl space type you described.

For vented crawl spaces, materials like fiberglass batts are common, but they don’t address moisture well—especially in humid areas. Unvented crawl spaces benefit from rigid foam board or closed-cell spray foam, which provide better moisture resistance. In humid regions, unvented (sealed) crawl spaces with vapor barriers and moisture-resistant insulation are often recommended to control humidity and prevent mold, while vented spaces may need careful attention to moisture barriers.

When you break down the material and installation costs, do you factor in DIY versus hiring a professional? I’m trying to understand the typical budget range for each approach and if there are hidden expenses homeowners should plan for.

The article provides cost ranges for both DIY and professional installation. DIY typically involves just material costs, which are lower, but you might need to buy or rent tools and allow more time for possible mistakes. Professional installation includes labor, which raises the price, but you’ll often get warranties and expert work. Homeowners should also budget for unforeseen issues like moisture problems, pest control, or repairs if any damage is discovered during insulation.

Can you provide more details on how the material and installation costs break down between vented and unvented crawl spaces? I’m trying to figure out which option would be more cost-effective in a humid region.

For vented crawl spaces, costs are usually lower because you typically insulate only the subfloor, using fiberglass batts or foam board. This can run $1–$3 per square foot installed. Unvented (sealed) crawl spaces require insulating the foundation walls, adding a vapor barrier, and often sealing vents. This method can cost $3–$7 per square foot, but it helps control humidity better, which is important in humid regions and can reduce long-term energy and moisture problems.

I noticed you touched on material and installation costs for insulating crawl spaces. Could you break down what the average homeowner in the US should expect to budget for encapsulating and insulating a 1000-square-foot crawl space?

For a 1000-square-foot crawl space, homeowners in the US typically spend between $7,000 and $15,000 for full encapsulation and insulation. This estimate includes vapor barrier installation, insulation materials (like foam board or spray foam), labor, and sealing. Costs can vary based on region, material choices, and whether you handle any prep work yourself. Always get multiple quotes to compare pricing in your area.

After insulating a crawl space as described, are there specific signs or indicators I should watch for over the next year to make sure it was done correctly and problems like moisture or pests aren’t coming back?

After insulating your crawl space, check regularly for any signs of dampness, musty odors, or water pooling, as these can signal lingering moisture issues. Watch for mold growth on insulation or framing, and keep an eye out for increased humidity inside your home. Also, look for evidence of pests, like droppings or chewed materials. If any of these appear, it could mean the insulation or vapor barrier needs attention.

I noticed you mentioned both vented and unvented crawl spaces. If my home’s crawl space is currently vented but I’m thinking of sealing it, what are the key steps or precautions I should be aware of to avoid future moisture problems?

If you’re sealing a vented crawl space, start by closing and sealing all exterior vents and gaps. Install a heavy-duty vapor barrier on the ground, overlapping and sealing seams, and run the barrier up the walls. Insulate the crawl space walls instead of the subfloor, and make sure to seal rim joists. Adding a dehumidifier can help manage any residual moisture. Address any drainage issues outside the home before you begin, so water can’t collect near the foundation.

I’ve heard conflicting things about insulating the crawl space floor versus the walls. Based on your guide, is one approach generally better for energy efficiency and air quality, especially in older homes with pest issues?

According to the guide, insulating the crawl space walls is usually more effective for energy efficiency and air quality, especially in older homes. Wall insulation creates a thermal barrier and helps seal out moisture and pests better than just insulating the floor. However, if your crawl space is vented or prone to severe pest issues, combining wall insulation with thorough sealing and pest control may offer the best results.

You mention that a lot of homeowners make mistakes with crawl space insulation. What are some signs I should check for in my crawl space now, to figure out if something was done wrong by previous owners, especially regarding moisture and air flow?

Look for signs like damp or musty smells, visible mold, wet or sagging insulation, and condensation on pipes or walls. Check if vents are sealed or open—improper venting can trap moisture or allow excessive airflow. Insulation should be tightly fitted without gaps or falling down. Any standing water, rusted metal surfaces, or warped wood also suggest previous mistakes. These checks can help you spot common installation or moisture issues.

I’m about to try insulating my vented crawl space, but I’m worried about accidentally making moisture issues worse. How do I know if I should seal the vents completely, or is there a safe way to keep some ventilation while still improving energy efficiency?

If you live in a humid or mixed climate, fully sealing crawl space vents and using a vapor barrier is usually safest to prevent moisture problems. Leaving vents open can invite humidity and mold. For most homes, encapsulation with sealed vents and adding a dehumidifier offers the best energy efficiency and moisture control. However, if you’re in a very dry climate, limited venting may be acceptable. Consulting a local professional can help you decide based on your specific conditions.

If a crawl space already shows signs of moisture intrusion, mold, or pests, should those issues be addressed before starting insulation, or can insulation help mitigate existing problems? I want to be sure I tackle things in the correct order.

It’s important to address any moisture, mold, or pest issues before you start insulating your crawl space. Insulating without resolving these problems can actually make things worse by trapping moisture or pests inside, leading to further damage. First, fix any water leaks or drainage issues, remediate mold, and deal with pests. Once those issues are resolved, you can move ahead with insulation to keep your crawl space dry and energy efficient.

You mentioned moisture intrusion as a big problem. If I already have some mold under my crawl space, should I address that before insulating, and if so, what is the best way to handle it?

Yes, it’s important to address any existing mold before insulating your crawl space. Insulating over mold can trap moisture and worsen the issue. The best approach is to have the mold professionally removed, especially if the affected area is large. After removal, make sure the space is completely dry and consider installing a vapor barrier to help prevent future moisture problems before proceeding with insulation.

The article mentions that vented crawl spaces are common in older homes but can have moisture problems. If my house has a vented crawl space in a humid area, should I consider sealing it first before insulating, or can I just add insulation as is?

If your house has a vented crawl space and you’re in a humid area, it’s generally better to seal the crawl space before adding insulation. Sealing helps prevent moisture from entering, which can otherwise get trapped in the insulation and lead to mold or other problems. Once sealed, you can insulate more effectively and improve your home’s energy efficiency and indoor air quality.

I noticed you mention material and installation costs—could you provide a rough estimate or price range for insulating a typical 1,500 square foot crawl space, and whether certain types of insulation have a higher upfront cost but better long-term savings?

For a 1,500 square foot crawl space, material and installation costs typically range from $1,500 to $6,000, depending on insulation type and local labor rates. Spray foam insulation generally has a higher upfront cost compared to fiberglass or rigid foam boards, but it often provides better air sealing and energy savings over time, potentially lowering your utility bills more effectively in the long run.

When you covered material and installation costs, did you include things like vapor barriers and drainage improvements alongside insulation, or is that calculated separately? I’m putting together a budget and want to make sure I’m not overlooking hidden expenses.

In the article, the material and installation cost estimates focused mainly on insulation itself, such as foam boards or fiberglass batts. Vapor barriers and drainage improvements weren’t included in those base figures, since those are often separate line items. When budgeting, it’s a good idea to account for the cost of the vapor barrier, any drainage work, and potential sealing materials in addition to the insulation.

I’m a bit confused about the difference between vented and unvented crawl spaces when it comes to insulation. If my crawl space has those small exterior vents but also sometimes gets damp, should I convert it to a sealed space before insulating, or can I just insulate as-is?

If your crawl space has exterior vents and tends to get damp, it’s usually best to convert it to an unvented (sealed) crawl space before insulating. Sealing the vents, adding a vapor barrier, and controlling moisture will help prevent mold and make insulation more effective. Insulating a vented, damp crawl space can trap moisture and cause problems, so sealing first is the safer approach.

After insulating and sealing a crawl space, are there specific maintenance steps or regular checks you recommend to ensure everything continues functioning properly over time, especially in more humid regions?

Yes, after insulating and sealing your crawl space—especially in humid areas—it’s wise to check for moisture or condensation every few months. Inspect for mold, musty odors, or pests. Make sure vents, vapor barriers, and insulation stay intact and dry. It also helps to monitor humidity levels and consider using a dehumidifier if moisture becomes an issue. Regular visual inspections and prompt repairs will keep everything functioning well.

The article mentions material and installation costs, but how much should I realistically budget for professionally insulating a 1000-square-foot crawl space? Are there major price differences between doing it myself versus hiring someone?

For professionally insulating a 1000-square-foot crawl space, you should budget anywhere from $2,000 to $8,000, depending on the materials used and your local labor rates. Doing it yourself could cut costs by half or more, but you’ll need to account for tool rental and your own time, plus careful installation to avoid issues later. Labor is the biggest added expense when hiring a pro.

Could you clarify what insulation materials are best for reducing allergens and improving air quality in crawl spaces? There are so many options mentioned that I’m not sure which would be most effective for that specific concern.

For reducing allergens and improving air quality in crawl spaces, closed-cell spray foam and rigid foam board insulation are often the best choices. These materials create an effective air and moisture barrier, which helps prevent mold, dust, and other allergens from entering your living space. Make sure to also seal vents and gaps, and consider using a vapor barrier for extra protection against moisture-related allergens.

You talk about common myths around crawl space insulation. Could you elaborate on one or two of the most persistent misconceptions you encounter, and explain how following those myths might negatively impact a homeowner in the long run?

One common misconception is that crawl spaces need to be ventilated to prevent moisture problems. In reality, open vents can actually bring in humid air, leading to mold and wood rot. Another myth is that only the floor above the crawl space needs insulation. Failing to insulate crawl space walls can result in heat loss and higher energy bills. Believing these myths can lead to unnecessary damage and wasted energy over time.

I noticed you mentioned that vented crawl spaces are common in older homes but are prone to moisture issues. If I have a vented crawl space in a humid area, is it better to convert it to an unvented one before insulating, or can I still insulate effectively as is?

In humid areas, it’s generally more effective to convert a vented crawl space to an unvented (sealed) one before insulating. This helps control moisture and prevents problems like mold or wood rot. Insulating a vented crawl space without sealing can trap moisture and reduce the benefits of insulation. Sealing the vents, adding a vapor barrier, and then insulating will give you the best results in terms of energy efficiency and home durability.

You talk about both DIY insulation and hiring a professional. For a 1,200-square-foot unvented crawl space, can you give a ballpark estimate of how much material and labor might cost separately? I want to compare if doing it myself is really worth it.

For a 1,200-square-foot unvented crawl space, material costs for DIY insulation (using rigid foam board or spray foam) typically range from $1,800 to $3,600. If you hire a professional, labor often adds another $2,000 to $4,000, bringing the total to about $4,000–$7,500. DIY can save significantly on labor, but consider the tools, time, and safety equipment you’ll need as well.

I’m trying to decide between vented and unvented crawl space options for my older home in a humid area. Does the guide suggest one is significantly better than the other for preventing moisture and pest problems, or does it vary by region?

The guide recommends unvented (sealed) crawl spaces for humid regions, especially in older homes. Unvented crawl spaces help control moisture and reduce pest issues by keeping humid air out and allowing for better insulation. While regional factors can matter, sealing is generally more effective than venting for moisture and pest prevention in humid climates.

Could you clarify whether your cost estimates for insulating crawl spaces include additional expenses like moisture barriers or pest control treatments? I want to make sure I’m budgeting for all the necessary steps, not just the insulation material itself.

The cost estimates in the article focus mainly on the insulation materials and basic installation. Expenses such as moisture barriers (like vapor barriers) and pest control treatments are not typically included in those figures. If you’re planning a comprehensive crawl space project, it’s wise to budget extra for these important steps, as they can significantly improve long-term performance and protection.

You mentioned that improper insulation materials or methods can lead to costly mistakes. Could you clarify which materials are most commonly misused in crawl spaces, and what issues those mistakes usually cause over time?

Commonly misused insulation materials in crawl spaces include fiberglass batts and open-cell spray foam. Fiberglass can absorb moisture and sag or even promote mold growth, especially if the crawl space is damp. Open-cell spray foam also absorbs moisture, which can lead to wood rot and poor air quality. These mistakes can result in higher energy bills, structural damage, and unhealthy indoor air over time.

When it comes to material costs for insulating a crawl space, do you have a ballpark estimate for a typical 1,000 square foot area? I’m trying to figure out what to expect if I decide to hire a professional versus doing it myself.

For a 1,000 square foot crawl space, DIY material costs usually range from $1,000 to $2,000, depending on the type of insulation (like foam board, spray foam, or fiberglass batts). If you hire a professional, expect total costs—materials plus labor—to run between $3,000 and $8,000. Variables include insulation type, local labor rates, and any extra work needed, like moisture barriers or repairs.

I’m curious about allergens and air quality since my family has sensitivities. When insulating a crawl space, are there specific materials or methods you recommend to help minimize dust and allergens entering the main part of the house?

For families with sensitivities, using closed-cell spray foam or rigid foam board insulation is a good choice, as these materials act as effective air barriers and minimize dust and allergen infiltration. Additionally, fully sealing any vents, gaps, and installing a quality vapor barrier across the floor and walls can help prevent outside air, moisture, and allergens from entering your living space.

You break down the types of crawl spaces and mention that moisture can be a big problem. Do certain insulation materials work better than others for controlling moisture issues, and how can I tell which material is best for my specific climate?

Some insulation materials are definitely better at handling moisture. Closed-cell spray foam and rigid foam boards are both excellent choices because they resist water absorption and create a moisture barrier. Fiberglass, on the other hand, can trap moisture and lead to mold. To choose the best material for your climate, check your local humidity levels and building codes; in humid areas, moisture-resistant foam options are often recommended. Consulting a local contractor can also help match insulation to your specific conditions.

Could you clarify what kind of maintenance or inspection is needed after insulating a crawl space? For example, how often should I check for moisture or pests, and are there any warning signs that the insulation needs to be replaced or repaired over time?

After insulating your crawl space, it’s important to inspect it at least twice a year. Check for moisture buildup, mold, or musty odors, which can signal leaks or inadequate ventilation. Look for signs of pests like droppings or chewed insulation. If you notice sagging, damp, or compressed insulation, or if sections have detached from the walls, it’s time to repair or replace those areas. Staying proactive with these checks helps keep your insulation effective and your crawl space healthy.

Could you provide more details on the average costs for insulating materials specifically for a medium-sized crawl space? I’m trying to budget for this project and want to avoid any surprise expenses down the line.

For a medium-sized crawl space, insulating materials typically cost between $1.50 and $3.50 per square foot, depending on your choice. Closed-cell spray foam is on the higher end, while fiberglass batts and rigid foam board are generally more affordable. For a 1,000 square foot crawl space, expect to spend around $1,500 to $3,500 on materials alone. Be sure to include costs for vapor barriers and fasteners if needed.

If my crawl space is vented and I live in a humid climate, should I be considering switching to a sealed crawl space before insulating, or is it enough to just use moisture-resistant insulation? What are the main trade-offs to consider?

In a humid climate, sealing your crawl space is usually more effective than just adding moisture-resistant insulation. Sealing helps prevent moisture, mold, and energy loss better than vented setups. The main trade-off is cost—sealing is more expensive upfront, but it can reduce long-term issues and improve indoor air quality. Simply using moisture-resistant insulation may not fully protect your home from humidity-related problems.

Can you elaborate on how to deal with existing moisture problems before insulating a crawl space? I have some mold and minor wood rot and want to make sure I don’t trap any issues inside.

Before insulating your crawl space, it’s essential to address moisture issues first. Start by fixing any water leaks or drainage problems around your foundation. Remove any standing water and use a dehumidifier to dry out the area. Clean mold with appropriate cleaners and replace any wood that shows signs of rot. It’s also a good idea to install a vapor barrier on the ground to control humidity. Only insulate after you’re sure the space is dry and all repairs are complete.

Could you give a ballpark idea of how much it might cost to have a professional insulate a crawl space versus doing it myself? I’m trying to figure out if DIY really saves that much once I factor in buying tools and materials.

Hiring a professional to insulate a crawl space typically costs between $3,000 and $8,000, depending on the size and complexity. If you do it yourself, material costs usually range from $800 to $2,000, plus tools if you don’t have them, which could add another $100–$300. DIY can save you quite a bit, but be sure to account for the extra time and effort involved.

If I start insulating my crawl space myself and run into mold or wood rot during the prep step, what’s the best way to handle that before moving forward? Should I call in a professional at that point or can I do remediation on my own?

If you discover mold or wood rot while preparing your crawl space, it’s important to address those issues before insulating. Small surface mold can sometimes be cleaned with a disinfectant, but if there’s extensive mold, structural damage, or a persistent moisture problem, it’s safer to contact a professional. They can ensure the area is properly treated and safe to insulate, which helps prevent future problems.

If my crawl space already has some signs of moisture or minor mold, should I address those issues before insulating, or can the right insulation also help solve them? What prep work is usually necessary in this situation?

It’s important to address any moisture or mold issues before adding insulation. Insulating over damp or moldy areas can trap moisture and make problems worse. You should first fix leaks, improve drainage, and remove any mold. Common prep work includes drying out the space, cleaning up visible mold, sealing any cracks, and laying a vapor barrier before installing insulation. This way, you’ll prevent future damage and make sure your insulation works effectively.

I noticed you mention both vented and unvented crawl spaces. If my older home has a vented crawl space but I want to improve energy efficiency, is it worth converting it to an unvented, encapsulated space before insulating? What are the main considerations?

Converting a vented crawl space to an unvented, encapsulated one can significantly improve energy efficiency and moisture control, especially in older homes. Main considerations include sealing all vents, installing a vapor barrier over the ground and walls, addressing any existing moisture issues, and possibly adding dehumidification. This process is more involved and costly than just insulating a vented crawl space, but it offers better long-term comfort and protection for your home.

I noticed you mention that vented crawl spaces are more prone to moisture issues, especially in humid climates. If my older house has a vented crawl space, is it worth the investment to convert it to an unvented style before insulating, or can the right insulation solve most of the moisture concerns?

Converting a vented crawl space to an unvented (sealed) design is generally considered the best approach for managing moisture, especially in humid regions. While proper insulation helps, vented crawl spaces can still allow humid air inside, leading to ongoing moisture problems. Sealing the crawl space and adding a vapor barrier before insulating usually offers better long-term protection for your home and improves energy efficiency.

Could you clarify whether the insulation approaches differ significantly between vented and unvented crawl spaces? I noticed the article mentions both types but I’m wondering if the recommended techniques or materials change depending on the crawl space type.

Yes, the insulation approach does differ between vented and unvented crawl spaces. For vented crawl spaces, insulation is typically placed between the floor joists, and you want to ensure vents remain open for airflow. In contrast, with unvented (sealed) crawl spaces, it’s recommended to insulate the crawl space walls and seal all vents to keep outside air out. Materials can also differ: rigid foam boards are common for walls in unvented spaces, while fiberglass batts are often used for vented spaces. Always use a vapor barrier on the ground for both types.

After sealing and insulating an unvented crawl space, are there specific ongoing maintenance tasks or checks I need to keep up with every year to avoid moisture or air quality issues over time?

Yes, ongoing maintenance is important for a sealed and insulated crawl space. Each year, check for any new cracks or gaps in the vapor barrier or insulation, and reseal if needed. Make sure drainage systems and sump pumps are working properly. Inspect for signs of moisture, mold, or pests, and keep vents, if any, clear. Regularly monitor humidity levels to ensure they stay in the safe range.

The article mentions that improper material choice can lead to costly mistakes. What are some of the most common insulation materials people use in crawl spaces, and which ones should I avoid if my main concern is moisture control?

Common insulation materials for crawl spaces include fiberglass batts, spray foam, rigid foam boards (like XPS or EPS), and mineral wool. If moisture control is your priority, it’s best to avoid fiberglass batts, as they absorb moisture and can promote mold. Instead, opt for closed-cell spray foam or rigid foam boards, which resist moisture and provide a better barrier against dampness.

I’ve read conflicting things about whether to seal or leave existing vents open after insulating a crawl space. Can you clarify what you recommend after insulation is installed, especially for older homes with vented crawl spaces?

After insulating a crawl space, it’s generally recommended to seal existing vents rather than leave them open, even in older homes. Sealing helps prevent moisture, pests, and drafts from entering, which improves energy efficiency and indoor air quality. Just make sure to address any existing moisture issues first and consider adding a vapor barrier and proper drainage if needed before sealing everything up.

You mention that material and installation costs are broken down in the guide. Could you give an estimate of the average total cost difference between insulating a vented crawl space versus encapsulating and insulating an unvented crawl space?

Insulating a vented crawl space typically costs between $1.50 and $3 per square foot, using basic insulation materials. Encapsulating and insulating an unvented crawl space is more comprehensive, averaging $7 to $14 per square foot, as it includes vapor barriers and sealing. The total cost difference depends on your crawl space size, but encapsulation is generally several times more expensive than just insulating a vented space.

When deciding between vented and unvented crawl spaces for insulation, are there certain climate zones in the US where one option is strongly recommended over the other? I’m trying to figure out what makes the biggest difference in humid versus dry regions.

Yes, climate plays a big role in choosing between vented and unvented crawl spaces. In humid or mixed-humid regions, unvented (sealed) crawl spaces are usually recommended because they prevent moisture and mold issues. In dry climates, vented crawl spaces can work, but unvented ones still offer better energy efficiency and moisture control. Local building codes and specific site conditions should also be considered when making your decision.

How much time should a first-time DIYer expect to spend on insulating a crawl space if they’re doing everything step by step like the guide describes? I’m trying to figure out if this is a weekend project or if I should plan for several days.

If you’re following the guide step by step and it’s your first time, expect to spend about 2 to 3 days on insulating a typical crawl space. The exact time depends on the crawl space size, how accessible it is, and how comfortable you are with the tools. For most, it’s a bit more than a weekend project, so setting aside a few days is a good idea.

I have a vented crawl space in an older home, and I’m worried about moisture buildup if I seal it up. Does insulating a vented crawl space require different materials or methods compared to an unvented one, and are there certain climates where vented spaces should never be sealed?

Insulating a vented crawl space does require a different approach than insulating an unvented (sealed) one. For vented crawl spaces, insulation is typically installed between the floor joists above the crawl space, and vapor barriers are used to help control moisture. If you choose to seal and insulate the crawl space (making it unvented), insulation goes on the walls, and all vents are closed. Sealing is not recommended in certain climates with high water tables or frequent flooding, as it can trap water inside. Always consider your local climate and consult with a professional before making changes.

When deciding between vented and unvented crawl spaces, how do I know which type is best for an older home in a humid area like the Southeast? Are there extra steps I should take to address existing moisture if I’m switching to an encapsulated system?

For older homes in humid areas like the Southeast, unvented (encapsulated) crawl spaces are usually more effective at controlling moisture and improving energy efficiency. Before encapsulating, it’s important to address any existing moisture issues—repair plumbing leaks, ensure proper exterior drainage, and dry out wet areas. Installing a vapor barrier and possibly a dehumidifier will also help maintain a dry crawl space. Consulting a professional for a thorough inspection is a good idea before making the switch.

I’m trying to decide between using a vented or unvented crawl space approach for my home in a humid area. Can you explain how insulation needs differ between these two types and if either one is better at preventing mold and moisture issues?

In humid areas, unvented (sealed) crawl spaces are generally more effective at preventing mold and moisture issues because they keep humid air out and allow for controlled conditioning. Insulation in unvented crawl spaces should be placed along the walls, not the floor, and a vapor barrier should be installed over the ground. Vented crawl spaces often require insulation between floor joists and can let in outside humidity, which may increase mold risk. Sealed crawl spaces with proper insulation and vapor barriers are usually better at moisture control.

With older homes that have existing vented crawl spaces, what’s the best way to address pest infestations before starting insulation work? Should certain insulation materials be avoided if there’s a history of rodents or insects in the crawl area?

Before insulating a crawl space in an older home, it’s important to first eliminate any pest infestations by sealing entry points, setting traps, or hiring a professional exterminator if needed. If there’s a history of rodents or insects, avoid using fiberglass batt insulation, as pests can nest in it. Rigid foam boards or closed-cell spray foam are better choices because they’re less attractive to pests and offer good moisture resistance.

You mention material and installation costs for insulating crawl spaces—could you give a rough estimate for a 1,500 square foot area? I’m wondering what kind of budget I should expect if I decide to hire a professional versus DIY.

For a 1,500 square foot crawl space, professional installation typically ranges from $3,000 to $7,500, depending on the insulation type and local labor rates. Doing it yourself can lower material costs to about $1,500 to $3,000. Keep in mind, hiring a pro adds to the cost, but ensures proper installation and may include warranties.

You mentioned potential cost breakdowns for insulating crawl spaces. For a small business property around 1,000 square feet, what would be the ballpark material and labor costs if I hire a professional versus doing it myself?

For a 1,000 square foot crawl space, hiring a professional typically costs between $2,000 and $7,000, depending on insulation type and local rates. Material costs alone for DIY are usually $500 to $1,500. Labor is the major added expense if you hire someone. Keep in mind, complex jobs or higher-grade materials can push costs higher.

You discuss how uninsulated crawl spaces can lead to poor air quality and allergens. If the crawl space already has signs of mold or mustiness, should insulation be prioritized before remediation, or vice versa?

If your crawl space shows signs of mold or mustiness, it’s important to address those issues before installing insulation. Mold and moisture problems should be remediated first to prevent trapping contaminants behind new materials, which could worsen air quality. After proper cleaning, drying, and possibly sealing, you can then insulate the space for best long-term results.

I’m curious about the cost side you mentioned—when breaking down material and installation costs for insulating a crawl space, do the figures differ significantly between vented and unvented (sealed) spaces? Are there considerations that could impact the total budget based on the type chosen?

Yes, costs can differ between vented and unvented crawl spaces. Insulating a vented crawl space usually involves using fiberglass batts, which are generally less expensive in both materials and installation. Unvented (sealed) crawl spaces often require foam board or spray foam, plus a vapor barrier and sometimes extra sealing work, making them pricier. The size of your space, local climate, and accessibility can also affect the total budget, especially for sealed crawl spaces where air and moisture control are critical.

Could you provide a ballpark estimate of how much it would cost in materials for an average-sized crawl space? I want to be sure I budget enough before starting this project myself.

For an average-sized crawl space of about 1,500 square feet, material costs typically range from $1,500 to $3,000. This estimate covers rigid foam board or spray foam insulation, vapor barriers, and sealing supplies. The total can vary depending on the insulation type you choose and whether you add extras like encapsulation. Buying materials during sales or at bulk rates may help reduce costs.

The article says that crawl spaces impact air quality and allergens in the house. After insulating, how quickly do most homeowners notice improvements in air quality, and are there any extra steps needed right after installation?

Most homeowners notice a change in air quality and a reduction in allergens within a few days to a couple of weeks after insulating the crawl space. Improvements can be more immediate if there were significant moisture or mold issues before. Right after installation, it’s a good idea to seal any remaining air leaks and run a dehumidifier if humidity is high. Regularly check the crawl space for any lingering moisture or odors.

As someone with an older home that has a vented crawl space, I’ve always heard conflicting advice on whether to seal the vents or keep them open. Can you clarify which approach is better in humid climates, and does this change the recommended insulation method?

In humid climates, it’s generally best to seal crawl space vents to prevent moisture from entering, which can lead to mold and wood rot. Sealing the vents turns the crawl space into a conditioned or encapsulated area. This approach typically pairs with insulating the crawl space walls instead of the floor, and adding a vapor barrier over the ground to control humidity.

You talked about material and installation costs for insulating crawl spaces. Could you give a bit more detail on the typical price range for doing it yourself versus hiring a professional, especially for an average-sized crawl space?

For an average-sized crawl space (about 1,000 square feet), DIY insulation costs typically range from $500 to $1,500, depending on materials like foam board or fiberglass batts. Professional installation generally costs between $2,000 and $4,000, which includes labor and sometimes higher-quality materials. The exact price depends on your region, the specific insulation type, and whether extras like vapor barriers are included.

I have a vented crawl space under my older home and I live in a pretty humid area. The article mentions that vented spaces are prone to moisture. Should I seal off those vents before insulating, or is there a way to safely keep them open?

In humid climates, it’s generally best to seal off crawl space vents before insulating. Open vents can let in moisture, leading to mold and structural issues. Sealing the vents, installing a vapor barrier, and then insulating creates a controlled environment that protects your home. Keeping vents open usually isn’t recommended in damp areas, as it can make moisture problems worse.

You mention that unvented (sealed) crawl spaces are often preferred in modern construction for better energy efficiency. Are there any specific building codes or regulations in the US that homeowners should be aware of before switching a vented crawl space to a sealed one?

Yes, there are building codes you should review before converting to a sealed crawl space. The International Residential Code (IRC), adopted by most US states, sets requirements for vapor barriers, insulation, drainage, and mechanical ventilation for unvented crawl spaces. Also, check your local building department for any additional regulations or permit needs, since some areas may have stricter guidelines or inspection processes.

You mentioned material and installation costs for insulating crawl spaces. Could you give a ballpark estimate of how much homeowners typically spend if they DIY versus hiring a professional?

For a DIY crawl space insulation project, homeowners usually spend between $0.50 and $2 per square foot, depending on the materials chosen. If you hire a professional, the total cost generally rises to $3 to $7 per square foot. Labor, prep work, and any repairs needed can increase the professional price, but DIY can save substantially if you’re comfortable with the work.

What’s the best way to tackle moisture issues in the crawl space before starting insulation? I know mold and rot are common problems, so should I use a vapor barrier, and are there signs I should look for that mean I need more extensive repairs first?

Addressing moisture is key before insulating your crawl space. Using a vapor barrier is highly recommended—it helps block ground moisture from rising. Before installing one, check for standing water, muddy soil, sagging insulation, or visible mold. These can signal drainage problems or existing damage that need fixing first. If you spot these issues, it’s wise to repair them before adding insulation or a vapor barrier to prevent future mold and rot.

Could you provide more detail on the typical material and installation costs for a small business property versus a standard home? I want to budget for this project and need a ballpark figure before reaching out to contractors.

For a standard home, insulating a crawl space typically costs between $1,500 and $4,000, depending on material choice and crawl space size. For a small business property, the range is often $2,500 to $7,000, since commercial spaces may have larger or uniquely shaped crawl spaces. The total includes insulation materials—like spray foam, rigid foam, or fiberglass—and labor. These are rough estimates; exact costs will vary based on location, access, and specific needs.

You mention that properly insulating a crawl space can help with moisture and allergens. Are there specific insulation materials that work best for moisture control, especially in humid areas, or is encapsulation always recommended?

For humid areas, rigid foam board insulation and closed-cell spray foam are often recommended because they resist moisture absorption better than fiberglass. However, encapsulation—sealing the crawl space with a vapor barrier—offers the best protection against moisture and allergens. Many homeowners use both: encapsulating first, then adding rigid foam or spray foam to insulate. This combination gives the most effective moisture control in humid climates.

When insulating a vented crawl space in a humid climate, is it better to convert it to an unvented (sealed) crawl space first? If so, what additional steps or materials would I need to factor in for that process?

In humid climates, it’s generally recommended to convert a vented crawl space to an unvented (sealed) one before insulating. This helps control moisture and prevents mold issues. To do this, you’ll need to seal all exterior vents and gaps, install a heavy-duty vapor barrier (typically 6-mil or thicker plastic sheeting) over the ground and walls, and consider adding a dehumidifier for ongoing moisture control. Insulation is then usually applied to the crawl space walls rather than the subfloor.

What’s the best way to handle moisture issues before starting insulation? Is it necessary to completely resolve minor leaks or damp spots first, or can certain insulation materials manage a bit of moisture?

It’s best to address any moisture issues, even minor leaks or damp spots, before adding insulation. Insulation materials generally aren’t designed to manage persistent moisture and trapping dampness can lead to mold or structural problems. Make sure to fix leaks, seal foundation cracks, and consider installing a vapor barrier. This will help your insulation work effectively and keep your crawl space dry.

If I have an older home with a vented crawl space, is it always better to switch to an unvented or sealed system, or are there situations where keeping the vents actually makes sense?

Switching to an unvented or sealed crawl space is recommended in most climates because it helps control moisture, improves energy efficiency, and reduces mold risk. However, in some very dry climates or homes with persistent flooding issues, keeping the vents might make sense. It’s important to consider your local climate, the condition of your home, and any drainage problems before making a decision. Consulting with a local expert can help you choose the best approach for your specific situation.

If I already have old fiberglass batts in my vented crawl space, do I need to remove them completely before switching to encapsulation, or can they be reused in some way? What are the risks of leaving old insulation in place?

For encapsulation, it’s best to remove old fiberglass batts from your vented crawl space. They tend to retain moisture, support mold growth, and can harbor pests, especially if they’re already sagging or dirty. Leaving them in place under a new vapor barrier can trap moisture and cause long-term problems. Reusing them isn’t recommended; starting fresh ensures a healthier, more effective encapsulation.

I’m concerned about indoor air quality and allergies in our house, and you mention that insulating the crawl space can help with this. Is there a specific type of insulation or vapor barrier that works best for reducing allergens and moisture in a humid area like the Southeast?

For humid regions like the Southeast, using a closed-cell spray foam or rigid foam board insulation is often best, as they resist moisture and mold growth. Pair this with a high-quality, reinforced vapor barrier (at least 12 mil thick) sealed over the ground and up the walls. This combination helps block moisture and reduces mold and allergen risks, improving your indoor air quality.

The excerpt mentioned a detailed breakdown of material and installation costs for insulating a crawl space. Could you give a ballpark estimate for a standard-sized crawl space and explain what might cause costs to go up or down?

For a standard-sized crawl space of about 1,000 square feet, material and installation costs typically range from $1,500 to $5,000. Costs can increase if your crawl space has high moisture issues, requires mold remediation, or is difficult to access. Using higher-end materials like spray foam instead of fiberglass batts will also raise the price, while basic materials and easy access can help keep expenses lower.

I have an older home with a vented crawl space and I’m confused about whether I should leave the vents open or sealed after insulating. The article mentions moisture issues with vented spaces, so should I also be encapsulating, or is insulation enough?

For older homes with vented crawl spaces, simply adding insulation may not fully address moisture problems. Sealing or encapsulating the crawl space after insulating is often recommended to control humidity and prevent mold or rot. Leaving vents open can still allow moisture inside, while encapsulation with a vapor barrier and sealed vents helps create a dry, energy-efficient environment. It’s a good idea to address both insulation and encapsulation together for the best results.

I’m worried about moisture and mold since my crawl space sometimes smells musty. Are there particular materials or steps in your process that are best for preventing mold growth when insulating in a humid area?

To prevent mold and moisture issues in humid crawl spaces, it’s important to use closed-cell spray foam or rigid foam board insulation, as they resist moisture absorption. Before insulating, make sure to seal any ground moisture with a heavy-duty vapor barrier covering the entire crawl space floor and up the walls. Also, address any drainage or ventilation problems, and ensure the space is dry before you start the insulation process.

After reading about the common mistakes people make with crawl spaces, I’m wondering what signs I should look for to know if my existing insulation needs to be replaced or upgraded, especially in older homes.

In older homes, signs that your crawl space insulation may need replacing include sagging or fallen insulation, visible mold or mildew, a persistent musty odor, drafts above the crawl space, or increased energy bills. You might also notice dampness or pest activity. Inspect for water damage or compressed and deteriorating material, as these are clear indicators that an upgrade or replacement is needed.

The article talks about material and installation costs, but I’m trying to stick to a tight budget. Are there any lower-cost insulation materials that are still effective for crawl spaces, and how can I balance affordability with long-term performance?

Fiberglass batts are usually the most budget-friendly insulation option for crawl spaces, and they can be effective if properly installed and kept dry. Rigid foam boards cost a bit more upfront but often provide better moisture resistance and long-term performance. To balance cost and effectiveness, focus on sealing air leaks first, then choose the best insulation type your budget allows, making sure it’s rated for use in damp areas.

Could you clarify whether the step-by-step insulation process in your guide is different for vented versus unvented crawl spaces, especially regarding moisture control and air sealing? I want to be sure I’m not missing any critical steps unique to each type.

Yes, the insulation process does differ between vented and unvented crawl spaces, particularly with moisture control and air sealing. For vented crawl spaces, the focus is usually on insulating the subfloor and ensuring proper ventilation. For unvented crawl spaces, you should insulate the walls, seal all vents and openings, and install a vapor barrier on the ground to control moisture. Carefully follow the steps specific to your crawl space type to avoid issues with mold or energy loss.

You mentioned that vented crawl spaces are more common in older homes and are prone to moisture issues, especially in humid climates. If someone lives in a drier region, would vented crawl spaces still present significant problems or can some of the insulation steps be skipped?

In drier regions, vented crawl spaces generally face fewer moisture problems than in humid areas. However, issues like heat loss and occasional moisture can still occur. While you might not need every moisture-control measure, it’s still important to properly insulate and seal gaps to improve energy efficiency and prevent pests or dust. Consider the specific conditions in your area before deciding which steps to skip.

I’ve heard that adding insulation to a crawl space can sometimes make moisture problems worse if it’s not done right. How do you make sure you’re controlling moisture properly when insulating, especially in a vented crawl space like the article describes?

You’re right that moisture control is crucial when insulating a vented crawl space. To prevent problems, first make sure any existing water leaks or drainage issues are fixed. Use a vapor barrier over the soil to block ground moisture, and extend it up the walls a few inches. Insulate between the floor joists with materials designed for crawl spaces, making sure not to block vents unless converting to an unvented system. Regularly check for signs of condensation afterward to catch issues early.

I noticed the guide covers both vented and unvented crawl spaces. How does the recommended insulation method differ between the two types, especially if you live in a region with hot, humid summers?

For vented crawl spaces, the guide suggests insulating the floor above the crawl space to keep humid air out, typically using fiberglass batts between joists. In unvented crawl spaces, it’s better to insulate the crawl space walls with rigid foam or spray foam, then seal the vents to prevent warm, moist air from entering. This is especially important in hot, humid climates to control moisture and reduce the risk of mold.

Your article touches on allergens and air quality. Are there particular insulation materials you recommend for homeowners with allergies, and are there any materials that should definitely be avoided in crawl spaces for that reason?

For homeowners with allergies, it’s best to use insulation materials that don’t trap dust or emit irritants. Closed-cell spray foam or rigid foam boards are good options because they don’t hold moisture or support mold growth. Try to avoid fiberglass batts, as they can release tiny fibers and sometimes harbor allergens if they get damp. Always look for materials labeled as low-VOC and ensure proper sealing to keep out dust and pests.

You mentioned providing a breakdown of material and installation costs for insulating crawl spaces. Could you clarify what kind of budget range homeowners should realistically expect, especially for professionally installed closed-cell spray foam versus DIY rigid foam board?

For professionally installed closed-cell spray foam in a crawl space, homeowners can expect to pay anywhere from $3 to $7 per square foot, depending on location and crawl space size. DIY rigid foam board is usually less expensive, typically $1 to $2 per square foot for materials, but you’ll need to factor in your own labor and any additional supplies like adhesive and tape. These costs can vary, but this range should help you plan your budget.

After insulating a crawl space, how soon should I expect to notice differences in indoor air quality or energy bills? I just want to know what kind of impact or improvements I might realistically see, and how long they typically take to show up.

You can typically notice improvements in energy bills within the first billing cycle after insulating your crawl space, as your heating and cooling systems won’t need to work as hard. Many people also report better indoor air quality within a few days to weeks, especially if moisture and drafts were issues before. The full benefits depend on factors like your home’s size, climate, and how well the crawl space was sealed and insulated.

Your guide mentions that material and installation costs can vary, but I’m on a pretty tight budget. Are there any specific insulation materials or methods you recommend for someone looking to maximize results while keeping costs low?

If you’re budget-conscious, consider using fiberglass batts or rolls, which are usually the most affordable insulation options for crawl spaces. They’re relatively easy to install yourself, which can save on labor costs. Make sure to use a vapor barrier to help control moisture. Focus on insulating the crawl space walls rather than the floor to maximize energy efficiency within a limited budget.

If my crawl space already has some moisture, should I address that before insulating, or can I do both steps at the same time? I’m concerned about trapping moisture inside and causing more problems down the road.

It’s important to address any moisture issues in your crawl space before installing insulation. Insulating over existing moisture can trap water, leading to mold, wood rot, and structural damage. Make sure to dry out the space and fix sources of moisture, such as leaks or drainage problems, first. Once the area is dry and sealed, you can safely proceed with insulation.

Could you outline what material or installation costs I should budget for if I hire a professional to insulate a small crawl space versus doing it myself? Are there common hidden expenses homeowners should expect?

For a small crawl space, hiring a professional typically costs between $2,000 and $4,000, including labor and materials like foam board or spray foam. DIY material costs usually range from $500 to $1,200, but you’ll need to invest time and possibly buy tools. Hidden expenses may include mold remediation, moisture barriers, disposal fees for old insulation, or upgrading access points. It’s important to inspect for these issues beforehand to avoid surprises.

I see you mentioned both vented and unvented crawl spaces—if my older home has a vented crawl space, do I need to close off the vents before insulating, or can I insulate with the vents still open?

For the best results, it’s recommended to close off the vents in a vented crawl space before insulating. Leaving vents open can let moisture in, which can reduce insulation effectiveness and lead to mold or wood rot. Sealing the vents and insulating the walls, rather than the subfloor, helps control humidity and improves energy efficiency.

You mentioned that unvented (sealed) crawl spaces are often preferred for energy efficiency. If my crawl space is currently vented, what are the key steps and challenges involved in converting it to a sealed, insulated space?

Converting a vented crawl space to a sealed, insulated one involves several key steps: first, you’ll need to close off all exterior vents and air leaks. Next, install a heavy-duty vapor barrier over the ground and up the walls. Insulate the crawl space walls—rigid foam board is often used. Finally, address moisture by adding a dehumidifier if needed. Common challenges include existing moisture or mold, limited access, and making sure all gaps are thoroughly sealed.

You mentioned that encapsulated or sealed crawl spaces are usually better for modern energy efficiency. If I have an older vented crawl space, is it possible to convert it to an unvented one, and what are the key steps or costs involved?

Yes, you can convert an older vented crawl space into an unvented (encapsulated) one. The main steps are sealing the vents, installing a vapor barrier on the floor and walls, insulating the walls, and possibly adding a dehumidifier. Costs vary depending on size and local labor, but homeowners typically spend $5,000 to $15,000. You might also need to address any drainage or moisture issues before starting.

I noticed you mention both vented and unvented crawl spaces, but I am not sure which type mine is. Is there an easy way for a homeowner to tell the difference before starting any insulation project?

You can usually tell if your crawl space is vented by looking for vents or small grates along the exterior walls of your home’s foundation. Vented crawl spaces have these openings to allow outdoor air in. If you don’t see any vents, and the crawl space is sealed off from outside air with insulation or barriers, it’s likely unvented. If you’re unsure, you might also check your home’s original building plans or ask a professional for a quick inspection.

You mentioned that certain insulation mistakes can lead to costly problems down the line. For a busy parent who’s interested in DIY but short on time, what are the biggest pitfalls to avoid when insulating a crawl space yourself?

If you’re short on time, the most important pitfalls to avoid are skipping a vapor barrier, using the wrong insulation type (like fiberglass batts in a damp space), and not sealing air leaks before insulating. These mistakes can cause moisture buildup, mold, or poor energy performance. Focus on air sealing, choosing rigid foam or spray foam, and adding a vapor barrier for the best results with minimal long-term issues.

We have a vented crawl space in our older home and struggle with humidity during the summer. Based on your guide, is it better to switch to an unvented (sealed) crawl space, or can vented spaces still be insulated effectively for moisture control?

Switching to an unvented (sealed) crawl space is usually more effective for controlling humidity and moisture, especially in older homes. Sealing the crawl space allows you to better manage air and moisture movement by adding insulation, a vapor barrier, and sometimes a dehumidifier. While insulating a vented crawl space helps, it rarely solves humidity problems as effectively as sealing. If moisture control is your top concern, a sealed system is typically recommended.

For homes with vented crawl spaces located in humid regions, what specific insulation materials or moisture barriers do you recommend to best address both heat loss and moisture intrusion discussed here? Are there differences in approach compared to drier climates?

In humid regions with vented crawl spaces, it’s important to use rigid foam board insulation or closed-cell spray foam, as these resist moisture while insulating effectively. Install a heavy-duty vapor barrier (at least 10-20 mil polyethylene) across the ground and extend it up the foundation walls, sealing all seams. Unlike in dry climates, you should focus more on moisture control—sometimes even considering encapsulation or adding dehumidifiers. In drier climates, insulation priorities shift more toward air sealing and thermal performance, with less emphasis on moisture barriers.

Could you give a rough estimate of how much it typically costs to insulate a standard-sized crawl space if I do it myself versus hiring a professional? Trying to figure out if the savings are really worth the extra effort.

For a standard 1,000-square-foot crawl space, DIY insulation usually costs between $500 and $1,500, depending on materials like foam board or fiberglass batts. Hiring a professional typically ranges from $2,000 to $4,000, which includes labor and materials. So, you could save $1,500 to $2,500 by doing it yourself, although it requires significant time and effort.

If we’re planning to do the insulation ourselves, what kind of installation time should we realistically expect for a medium-sized crawl space? I need to balance this project with work and family commitments, so any estimate helps.

For a medium-sized crawl space, you can typically expect DIY insulation to take between 1 and 2 full days, depending on your experience and how accessible the area is. If you work in half-day sessions, plan for about 3–4 sessions. Setting aside extra time for prep—like clearing out debris and ensuring the area is dry—will also help the process go more smoothly.

You talk about how insulating your crawl space helps with moisture intrusion and air quality. Are there any specific signs I should look for to know if moisture or mold is already a problem before I start insulating?

Yes, there are some clear signs to watch for before insulating your crawl space. Check for musty odors, visible mold on wood or insulation, water stains, damp or soft wood, and condensation on pipes or walls. Peeling paint or rust on metal surfaces can also signal excess moisture. If you spot any of these, address the moisture issue and any mold before adding insulation for the best results.

Could you explain a bit more about the material cost breakdown you mentioned? I’m trying to set a realistic budget for my project, but I’m unsure how much extra to include for things like vapor barriers or sealing supplies beyond the main insulation materials.

Certainly! Besides the main insulation (which typically costs $0.50–$2.00 per square foot depending on type), you’ll want to budget around $0.15–$0.50 per square foot for a vapor barrier. Sealing supplies like caulk, spray foam, or tape can add another $50–$150 total, depending on crawl space size. It’s smart to add an extra 10–15% to your total budget to cover unexpected needs or minor repairs.

If I find some signs of mold or mild wood rot when I assess my crawl space, should I deal with those problems before insulating, or is it possible to address them at the same time? What’s the recommended order of steps for tackling both issues?

It’s important to address mold and wood rot before installing insulation. Dealing with these issues first ensures you don’t trap moisture or further damage beneath the new materials. Start by removing any mold and repairing or replacing rotted wood, then let the area dry thoroughly. Once the crawl space is clean and dry, you can move on to insulating. This order helps protect your home’s structure and ensures the insulation works effectively.

If my home has a vented crawl space and I’m worried about moisture causing mold, is it better to just seal it entirely before insulating, or are there situations where leaving it vented makes sense?

Sealing your crawl space before insulating is usually the best way to control moisture and prevent mold, especially in humid areas. Venting can sometimes worsen moisture issues. However, leaving it vented might make sense in very dry climates or older homes specifically designed for ventilation. For most homes, though, sealing the crawl space and adding a vapor barrier is the safer choice for mold prevention.

The article highlights moisture intrusion as a major issue in crawl spaces. Before starting any insulation, are there signs or tests you recommend to determine if existing moisture problems need to be addressed first? If so, what steps should I take if I do find elevated moisture levels?

Absolutely, checking for moisture is essential before insulating. Look for visible signs like water stains, musty odors, mold growth, or condensation on surfaces. You can also use a moisture meter to check wood or concrete. If you find elevated moisture, address the source first—fix leaks, improve drainage, install a vapor barrier, and consider adding ventilation or a dehumidifier if needed. This ensures your insulation won’t trap moisture or cause future problems.

If my crawl space has already had some moisture issues in the past but seems dry now, should I go with a sealed crawl space or stick with vented? How can I be sure I won’t trap future moisture inside?

Since your crawl space has had moisture issues before, a sealed (encapsulated) crawl space is usually safer, as it helps prevent future moisture and mold problems. To avoid trapping moisture, make sure to address any water entry sources first, use a high-quality vapor barrier, and install a dehumidifier if recommended. Having a professional assess your crawl space is also a good step to ensure proper sealing and ventilation where needed.

If my crawl space already has some minor mold from previous moisture intrusion, should I handle that before starting the insulation process? Are there particular products or steps you recommend to make sure the mold doesn’t return?

It’s important to address any existing mold before insulating your crawl space. First, clean the affected areas with a mold cleaner or a diluted bleach solution, making sure to wear protective gear. Let everything dry thoroughly. Afterward, consider applying a mold-resistant sealant to the surfaces. To prevent mold from returning, fix any moisture sources, use a vapor barrier, and ensure proper ventilation or install a dehumidifier if needed.

You mention that moisture can lead to problems like mold and wood rot. How do you recommend homeowners check for existing moisture issues before starting insulation, and what should be done if they find some?

To check for moisture issues in your crawl space, look for signs like damp insulation, water stains, condensation, musty odors, and visible mold or mildew on wood or walls. You can also use a moisture meter to test wood and subfloor surfaces. If you find moisture problems, address the source first—repair leaks, improve drainage, and consider installing a vapor barrier. Only start insulating after the space is completely dry and any mold has been properly treated or removed.

The article mentions both vented and unvented crawl spaces, but I’m not sure how to tell which type I have in my older house. Are there specific signs or features I should look for before starting insulation work?

To determine your crawl space type, look for exterior vents along the foundation walls—these are a clear sign of a vented crawl space. Unvented crawl spaces usually have sealed walls with no exterior vents, and may also have a vapor barrier on the floor and insulation along the walls. Checking for these features will help you decide how to proceed with insulation.

I noticed you mentioned both vented and unvented crawl spaces with different moisture issues. For someone with an older vented crawl space in a humid region, is it better to seal and insulate, or just add insulation while keeping the vents? What are the main risks with each approach?

For an older vented crawl space in a humid area, sealing and insulating is usually more effective at controlling moisture and improving energy efficiency. Simply adding insulation while keeping the vents can still allow humid air in, leading to mold and wood rot. Sealing and insulating reduce these risks but require careful moisture management, like adding a vapor barrier and possibly a dehumidifier. The main risk with sealing is trapping moisture inside if not done properly, while vented spaces risk ongoing humidity problems and potential structural damage.

After insulating a crawl space, what should homeowners watch for in the first few months to make sure everything was done correctly? Are there any clear warning signs of moisture problems or insulation failures that people overlook?

In the first few months after insulating a crawl space, check for musty odors, dampness, or visible mold, which could signal moisture issues. Also watch for condensation on pipes, sagging or wet insulation, and changes in indoor humidity. If floors above feel colder than expected or energy bills don’t improve, it could indicate insulation gaps or failures. Regularly inspect for pests, as they sometimes find entry points through compromised insulation.

If a crawl space already has some moisture problems, should insulation be installed before or after fixing those issues? I want to avoid making any mistakes that could trap more moisture or lead to mold.

It’s important to address any moisture problems before installing insulation in your crawl space. Fixing leaks, improving drainage, sealing vents, and possibly installing a vapor barrier will help prevent moisture from being trapped and causing mold or other issues. Once the area is dry and moisture-controlled, you can safely install insulation for the best results.

I’m a bit confused about the right type of insulation for crawl spaces. The article mentions different materials and methods, but how do I decide between using foam board, spray foam, or fiberglass for an unvented crawl space in a humid climate?